#01

Tsitsi Jaji &

Antawan I. Byrd

29 06 2021

Tsitsi Jaji has given readings at the UN headquarters, UNESCO, and the U.S. Library of Congress, among others. Her most recent volume of poetry, Mother Tongues, received the Cave Canem Second Book Prize, and was published by Northwestern University Press in 2019. She is also the author of Beating the Graves and a chapbook, Carnaval, published in the first New Generation African Poets box set, both from the African Poetry Book Fund. She earns her living as an associate professor at Duke University. Her academic book, Africa in Stereo: Music, Modernism and Pan-African Solidarity, is based on research in Ghana, Senegal and South Africa. It received the African Literature Association’s First Book Award, and an honorable mention from the Association of Comparative Literature and Society for Ethnomusicology. Jaji was born and raised in Zimbabwe.

Antawan I. Byrd is associate curator of Photography and Media at the Art Institute of Chicago where he recently co-curated The People Shall Govern! Medu Art Ensemble and the Anti-Apartheid Poster (2019). He co-curated the 2nd Lagos Biennial of Contemporary Art (2019), Kader Attia: Reflecting Memory (2017) at Northwestern’s Block Museum of Art, and was an associate curator for the 10th Bamako Encounters, Biennale of African Photography (2015). From 2009 to 2011, he was a Fulbright fellow and curatorial assistant at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos. A doctoral candidate in art history at Northwestern University, Byrd is currently completing a dissertation that explores the role of listening in sixties-era politics as manifested through art and aesthetic practices across the Afro-Atlantic world.

Antawan I. Byrd is associate curator of Photography and Media at the Art Institute of Chicago where he recently co-curated The People Shall Govern! Medu Art Ensemble and the Anti-Apartheid Poster (2019). He co-curated the 2nd Lagos Biennial of Contemporary Art (2019), Kader Attia: Reflecting Memory (2017) at Northwestern’s Block Museum of Art, and was an associate curator for the 10th Bamako Encounters, Biennale of African Photography (2015). From 2009 to 2011, he was a Fulbright fellow and curatorial assistant at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos. A doctoral candidate in art history at Northwestern University, Byrd is currently completing a dissertation that explores the role of listening in sixties-era politics as manifested through art and aesthetic practices across the Afro-Atlantic world.

#01

Tsitsi Jaji &

Antawan I Byrd

in conversation podcast 52’ 18”

mujejeje, singing stones, form the departure point in a conversation between Jaji & Byrd, as they journey into the realm of acoustic archaeology, and then navigate through photography to traverse Zimbabwe in 1965 -- what was then colonial Rhodesia at a critical moment in history, UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence) -- to 1960s independent Mali, Senegal and Algeria. Through the medium of radio, they explore the role of listening in politics and social life; how memory and senses intertwine; and how these are encoded into images, collective and everyday practices.

#01

Tsitsi Jaji &

Antawan I Byrd

in conversation transcript 52’ 18”

Tsitsi Jaji It's so exciting to be here and in conversation with you Antawan and to be part of Njelele Art Station! We're glad to be here, and I know we've been invited to talk about this amazing starting point of stones that make sounds, that sing. Anytime you're talking about Zimbabwe, you're thinking of the "houses of stone" and of the incredible granite and dolomite and other outcroppings that we grew up seeing as we drove past, taking for granted. And knowing there's so many deep mysteries connected to and spiritual connections as well. But for me, coming to this idea of singing stone happened as I was finishing up a book about Pan-Africanism, in which Zimbabwe played a small but important role, it was the opening and the end. I was remembering Independence Day, and the fact that my brother got to go to the celebrations with my father at Rufaro Stadium. He's two and a half years younger than me, and he was barely two years old and so this has remained a troubling issue. I wanted to be there as part of history and of course, Bob Marley was so important in that moment. So I wanted to finish also with Zimbabwe in this book, and I had read about these stones, stone gongs, that you could make sound by hitting hollowed granite rock with another rock, and it would just ring. This was so moving to me, this idea that stones literally sing and that for many centuries, particular places -- it's known that there are some at Khami, near Great Zimbabwe, in the Eastern Highlands... So this resonating of our environment was so powerful to me and it connects to something I was thinking about in stereo as sound in a kind of surround audio environment, that we experience the original kind of stereo by two different signals of sound being slightly out of phase. And so this idea that one starts to feel in a kind of collective space through hearing difference is very powerful to me and I love the fact that we have this instance in Zimbabwe. I know, you've also thought a lot about nationhood, and sound in Zimbabwe and I wonder if you'd share a little bit about what you're finding in your studies with radio and other audio technologies.

Antawan I. Byrd I would say that, you know, I similarly I developed this interest in the stone gongs or rock gongs, in part because, when Dana first mentioned this idea for a conversation, and she described mujejeje, I started reading about, you know, this field called "acoustic archaeology," and how there's this desire on the part of a lot of archaeologists to look at stones as a way of trying to reconstruct these various sort of intangible, sonic or acoustic histories. Some of this research has gone very deep into late Stone Age histories, or the Dynastic Period in Egypt – looking at the representation of sound technologies, on rock formations and caves and things like that, and trying to measure echoes. And what interests me about this research is how it intersects visuality and sound in a very deep and historical way, but also the resonances of these methods for thinking about such intersections during the mid twentieth century. And so in the case of Zimbabwe with the UDI in 1965, I've been really interested in how people began to think about the intersections of nationhood and politics through sound. And one of the earliest objects that I've encountered - that's been really insightful for me - is this photograph that photojournalist Marion Kaplan made in Zimbabwe in 1965, in Cecil Square. I want to share the image so that we could talk about it.

Tsitsi Jaji I'd love that.

Antawan I. Byrd I would say that, you know, I similarly I developed this interest in the stone gongs or rock gongs, in part because, when Dana first mentioned this idea for a conversation, and she described mujejeje, I started reading about, you know, this field called "acoustic archaeology," and how there's this desire on the part of a lot of archaeologists to look at stones as a way of trying to reconstruct these various sort of intangible, sonic or acoustic histories. Some of this research has gone very deep into late Stone Age histories, or the Dynastic Period in Egypt – looking at the representation of sound technologies, on rock formations and caves and things like that, and trying to measure echoes. And what interests me about this research is how it intersects visuality and sound in a very deep and historical way, but also the resonances of these methods for thinking about such intersections during the mid twentieth century. And so in the case of Zimbabwe with the UDI in 1965, I've been really interested in how people began to think about the intersections of nationhood and politics through sound. And one of the earliest objects that I've encountered - that's been really insightful for me - is this photograph that photojournalist Marion Kaplan made in Zimbabwe in 1965, in Cecil Square. I want to share the image so that we could talk about it.

Tsitsi Jaji I'd love that.

Marion Kaplan, 11 November 1965--under the eyes of two policemen, Africans await UDI developments (unilateral declaration of independence) in Salisbury, Rhodesia, now Harare, Zimbabwe, 1965. © Marion Kaplan

Antawan I. Byrd For me, what's so magical about the image is the way that the radio set is positioned directly in the centre of the image. And it's almost mediating this sort of very intense political moment between the state which is represented by the two police officers in the foreground, and all the seated black Zimbabwean subjects on the lawn. Everyone has this sort of like pensive expression on their faces, and you can't quite tell at what moment the photograph was taken—whether or not it's after the fate of Southern Rhodesia is announced by Ian Smith, or if it's the moment before, or if they're actually listening to anything at the time that the image was taken. And for me, that uncertainty is quite magical, because I think it speaks to how all photographs, in some way, are bound by a certain degree of uncertainty, this inability to know the precise circumstances under which a picture was made.

Tsitsi Jaji It's so amazing to me looking at this, you know, we’ve got these two Rhodesian policemen wearing what for any Zimbabwean is stereotypical dress. You know, they've got their socks knee-high and their shorts that are quite fitted, and their safari shirts on and their caps, you know, and with their backs turned to us, the audience and their hands clasped like that behind their backs. So there's both this sense of standing over the Zimbabwean men, for the most part, I don't see any women listening, but the sense that they're standing over them, but also that they are looking backwards. They're not looking to the future, you know, and that a kind of collective listening is happening among all of the men who are seated, hearing one version of what nationhood means, but also sitting there in another version of it, right. So there's the one radio that supposedly defines what the future is going to be or mediates a future even between these Rhodesian enforcers of law and order such as it was construed to be under UDI. And then this large group of men arrayed sitting on the ground. Their posture reminds me also of other spaces where you see people seated in Zimbabwe, listening very sensitively, not just to technology but also to debate among community members reaching certain kinds of decisions. And then it's also as I'm looking at this, I'm also seeing the way those trees behind them, these fir trees that are certainly not indigenous have been shaped in such a manicured way, and how much of the ecological environment of Zimbabwe has been impacted by the traces of colonisation. And yet the materiality of rock really is one of the undeniable aspects of what outlasts these, the sort of human scale, of intervention. And then I think in an earlier conversation, you had remarked Antawan on the the steps that we see here, which in a lot of ways look or the small wall that looks a lot like the structures of Great Zimbabwe. So this was an image I had never seen before. And I just, I thank you for it. And it's an amazing way to see what's already also kind of located place that is so resonant for Zimbabweans and Harare Gardens, and Unity Square and being so close to the parliament and to Monomatapa Hotel and so many other aspects. I mean, it's the radio is at the centre of this image and this space is at the centre of a particular version of nationhood and aspiration for self determination, which there was going to be a struggle over. I mean, there had been already, going back to the late 1800s. But that was a turning point.

Antawan I. Byrd I love the way that you point out this tension in discussing the character of the image, and these manicured trees in the background. I had an email exchange with the photographer, Marion, about this image, and one of the things I was really curious about was whether or not it was just a kind of an impromptu decisive moment, or if she was consciously trying to compose the picture as a way of, you know, really giving a sense of this standoff or this tension. And she said, it was in many ways, happenstance. Suggestive of this, I've always liked how you see, in the foreground, the displaced dirt that's spilling over this area where the trees are sort of faded. And then you have dirt also between the two officers and the just before the wall. And so that, in some sense, stands in contrast to the very manicured nature of the trees in the background. And even the way the subjects are all sort of positioned in a uniformed and contemplative way.

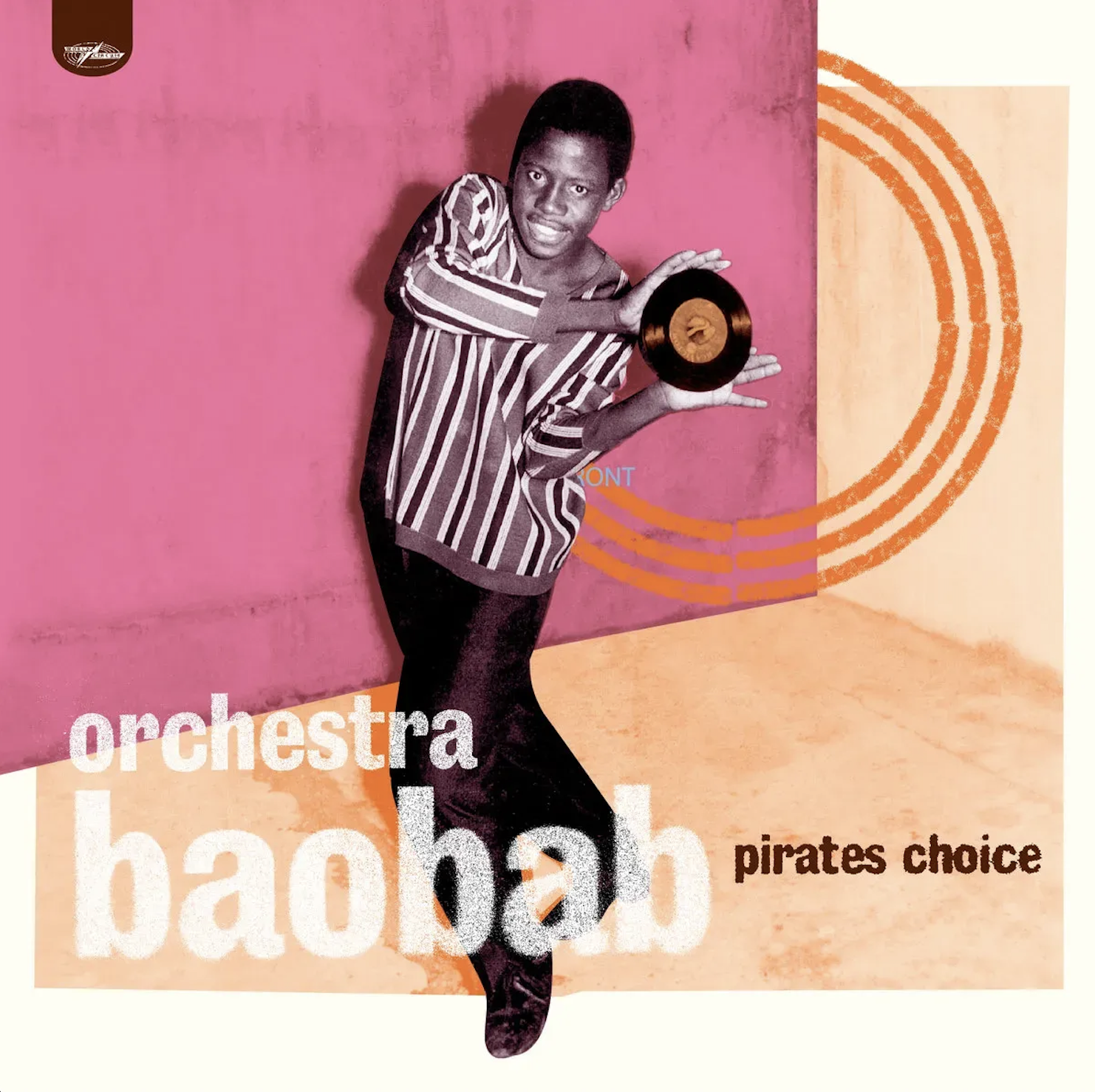

Tsitsi Jaji I had not noticed the dirt, but that's such a perceptive way of looking. I am enjoying talking to a specialist in visual art as well as sound and the way that you look at this. You know, it's funny, because one of the other things that we share in common is a love for images of people listening and enjoying music. I'm thinking about the photographs by so many people and you'll name some of the ones that you're looking at, but the ones that I first encountered of Malik Sidibé, people listening to records, and it's reminding me that one sees them in studio spaces, like this wedding party, but also, well, this one looks more like a live event. And one that has become so iconic, as you're showing here with a record that I really love, "Pirates Choice." But also many images of people listening outdoors. We see people in their ecological environment, and music is marking the space and etching their taste, their sociality, their connection, that's not an interrupted connection. It's like a given right to the space and the environment in which they're living.

I wonder if I could share with you for a moment a poem that I'd written about Malik Sidibé in particular, and I'm thinking also about a way that this listening, captured in so many ways, what it meant to be young at a particular moment. Francophone Africa, kind of got their independence, such as it was, and of course, is the critique of France Afrique and this sort of thing, but they got it earlier than, say Zimbabwe did. And so this sense also of the moment of soul music, as coinciding with independence, I think is so moving in this. So this is a poem I call "Malik Sidibé Camera Calls" And I have to share with you one of the most exciting things for me is that this was included in a exhibition with the Bamako photography Biennale on the year when [Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung] a curator at Savvy Contemporary in Berlin was curating this.

And as I was writing this poem, one of the things that really moved me is that so many of those photographs are in black and white, just like the one that you shared with us. And there's a sense that sound and listening is ephemeral. Black and white photography says something archival, says something about living in history and a history that counts. And that is quite generative. You know, I can also say I wrote a book in which I talk about these mujejeje. And this was the cover of it, which I love. It's actually a Malik Sidibé image. And one of the most moving things I can say is that a wonderful Malian documentary filmmaker, Cherif Keïta, who's made a film about the wife of John Dube, the founder of what became the ANC and a woman who had been forgotten, Nokutela Dube. So this Cherif, this Cherif Keïta also knew Malik Sidibé and gave him a copy of my book before Sidibé passed away. And you know, these are the kinds of things that one can't ask of life, but when they happen, they stay with you. So a few years ago, when the book was coming out, I found a copy of the LP that this woman is holding. She's clearly in Francophone West Africa because it says, “Dansez le twiste avec Ray Charles” and I was expecting it to be black and white, when it came it had this very garish pink lettering on it. And, you know, I went to Arundel, which my Zimbabwean friends will know as the "Pink Prison." So pink was not the colour I was looking for to think about how it migrated from this pink colour world that we think of as a moment of technicolour to black and white, which one could call an outmoded medium of the past. But there is so much the medium of saying here: this present matters, this present is entering history, and we are making history. And they're making it by listening to music. I love it.

Tsitsi Jaji It's so amazing to me looking at this, you know, we’ve got these two Rhodesian policemen wearing what for any Zimbabwean is stereotypical dress. You know, they've got their socks knee-high and their shorts that are quite fitted, and their safari shirts on and their caps, you know, and with their backs turned to us, the audience and their hands clasped like that behind their backs. So there's both this sense of standing over the Zimbabwean men, for the most part, I don't see any women listening, but the sense that they're standing over them, but also that they are looking backwards. They're not looking to the future, you know, and that a kind of collective listening is happening among all of the men who are seated, hearing one version of what nationhood means, but also sitting there in another version of it, right. So there's the one radio that supposedly defines what the future is going to be or mediates a future even between these Rhodesian enforcers of law and order such as it was construed to be under UDI. And then this large group of men arrayed sitting on the ground. Their posture reminds me also of other spaces where you see people seated in Zimbabwe, listening very sensitively, not just to technology but also to debate among community members reaching certain kinds of decisions. And then it's also as I'm looking at this, I'm also seeing the way those trees behind them, these fir trees that are certainly not indigenous have been shaped in such a manicured way, and how much of the ecological environment of Zimbabwe has been impacted by the traces of colonisation. And yet the materiality of rock really is one of the undeniable aspects of what outlasts these, the sort of human scale, of intervention. And then I think in an earlier conversation, you had remarked Antawan on the the steps that we see here, which in a lot of ways look or the small wall that looks a lot like the structures of Great Zimbabwe. So this was an image I had never seen before. And I just, I thank you for it. And it's an amazing way to see what's already also kind of located place that is so resonant for Zimbabweans and Harare Gardens, and Unity Square and being so close to the parliament and to Monomatapa Hotel and so many other aspects. I mean, it's the radio is at the centre of this image and this space is at the centre of a particular version of nationhood and aspiration for self determination, which there was going to be a struggle over. I mean, there had been already, going back to the late 1800s. But that was a turning point.

Antawan I. Byrd I love the way that you point out this tension in discussing the character of the image, and these manicured trees in the background. I had an email exchange with the photographer, Marion, about this image, and one of the things I was really curious about was whether or not it was just a kind of an impromptu decisive moment, or if she was consciously trying to compose the picture as a way of, you know, really giving a sense of this standoff or this tension. And she said, it was in many ways, happenstance. Suggestive of this, I've always liked how you see, in the foreground, the displaced dirt that's spilling over this area where the trees are sort of faded. And then you have dirt also between the two officers and the just before the wall. And so that, in some sense, stands in contrast to the very manicured nature of the trees in the background. And even the way the subjects are all sort of positioned in a uniformed and contemplative way.

Tsitsi Jaji I had not noticed the dirt, but that's such a perceptive way of looking. I am enjoying talking to a specialist in visual art as well as sound and the way that you look at this. You know, it's funny, because one of the other things that we share in common is a love for images of people listening and enjoying music. I'm thinking about the photographs by so many people and you'll name some of the ones that you're looking at, but the ones that I first encountered of Malik Sidibé, people listening to records, and it's reminding me that one sees them in studio spaces, like this wedding party, but also, well, this one looks more like a live event. And one that has become so iconic, as you're showing here with a record that I really love, "Pirates Choice." But also many images of people listening outdoors. We see people in their ecological environment, and music is marking the space and etching their taste, their sociality, their connection, that's not an interrupted connection. It's like a given right to the space and the environment in which they're living.

I wonder if I could share with you for a moment a poem that I'd written about Malik Sidibé in particular, and I'm thinking also about a way that this listening, captured in so many ways, what it meant to be young at a particular moment. Francophone Africa, kind of got their independence, such as it was, and of course, is the critique of France Afrique and this sort of thing, but they got it earlier than, say Zimbabwe did. And so this sense also of the moment of soul music, as coinciding with independence, I think is so moving in this. So this is a poem I call "Malik Sidibé Camera Calls" And I have to share with you one of the most exciting things for me is that this was included in a exhibition with the Bamako photography Biennale on the year when [Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung] a curator at Savvy Contemporary in Berlin was curating this.

Malik Sidibé's Camera Calls

Come to me, all you ochred yellows,

and you swaths of Indigo-bled purple.

You too poor for boubous

and you cotton blenders. Catch

your full skirts, young women,

or smooth the curves of your taille-basse.

The negative will drain

whatever brassy print

your tailor settled on,

and wash your sun skin-bright.

The darker the room,

the groovier the glint

of a flirting eye, a glossed nail,

a lavish twist, done

just right. Night time is

the right time

to be young/gifted/ and black,

to mash, grind,

funk up the chequered floor

and shake all living colour

off, for the silvery surface of

infinity. Hang, here

after the shoot, if you wish -

the beat goes on.

And as I was writing this poem, one of the things that really moved me is that so many of those photographs are in black and white, just like the one that you shared with us. And there's a sense that sound and listening is ephemeral. Black and white photography says something archival, says something about living in history and a history that counts. And that is quite generative. You know, I can also say I wrote a book in which I talk about these mujejeje. And this was the cover of it, which I love. It's actually a Malik Sidibé image. And one of the most moving things I can say is that a wonderful Malian documentary filmmaker, Cherif Keïta, who's made a film about the wife of John Dube, the founder of what became the ANC and a woman who had been forgotten, Nokutela Dube. So this Cherif, this Cherif Keïta also knew Malik Sidibé and gave him a copy of my book before Sidibé passed away. And you know, these are the kinds of things that one can't ask of life, but when they happen, they stay with you. So a few years ago, when the book was coming out, I found a copy of the LP that this woman is holding. She's clearly in Francophone West Africa because it says, “Dansez le twiste avec Ray Charles” and I was expecting it to be black and white, when it came it had this very garish pink lettering on it. And, you know, I went to Arundel, which my Zimbabwean friends will know as the "Pink Prison." So pink was not the colour I was looking for to think about how it migrated from this pink colour world that we think of as a moment of technicolour to black and white, which one could call an outmoded medium of the past. But there is so much the medium of saying here: this present matters, this present is entering history, and we are making history. And they're making it by listening to music. I love it.

Antawan I. Byrd I think that's fantastic, Tsitsi. First, I want to say thanks for sharing that poem. I mean, as you were reading it, the first thing that came to mind was the relationship between colour that you're describing and some of the images, the yellow ochres, for example, or the imagined sort of colours of the subjects’ clothing, and how that stands in relation to the black and white nature of the images. Here so many things come to mind. I mean, I think about Malik Sidibé and other portraitists, and how their clients would take their photographs to framers and have them customized with unique glass painted frames featuring vibrantly beautiful colours that would adorn the image. And so you'd have this black and white picture in the centre and then this really beautiful colorfully ornate frame in many cases. And then also in some cases, they would take the photographs themselves to studio photographers or to framers and have them hand-coloured with gold to emphasize the ornate jewelry their wearing or have their fingernails painted. So there was a sense on the one hand of appreciating the black and white sort of character but also wanting to amplify the picture aesthetically through the addition of colour. And it also makes me think about something that we were talking about last week of how, you know, over the last, I would say last two decades, there has been this effort to reissue a lot of mid 20th century music by different record companies who remaster the recordings. And on a fairly consistent basis they reference and make use of these mid-century photographs, but they also try to amplify them through the effects of color. For instance, here we're looking at the cover of [Orchestra Baobab’s] Pirates Choice. And so there's a sense that while the image itself is enough to take us back to that moment, there’s also a need to rejuvenate or enliven it through, you know, overlaying colours. And so I think that's quite interesting.

Cover of Orchestra Baobab’s Pirates Choice (Nonesuch Records, 2006) featuring Malick Sidibé’s Drissa Balo Wedding Party (1967)

Tsitsi Jaji Can I ask you how you came to be interested in this particular form, the visual representations of listening? It's such a fascinating way to think about senses being intertwined. And a relation to history. I was so interested to hear your comments about acoustic archaeology. And there's a way in which this is, I mean, it's acoustic photography, acoustic archiving, audio visual archiving, multimedia snapshots. Yeah, I just want to hear about that.

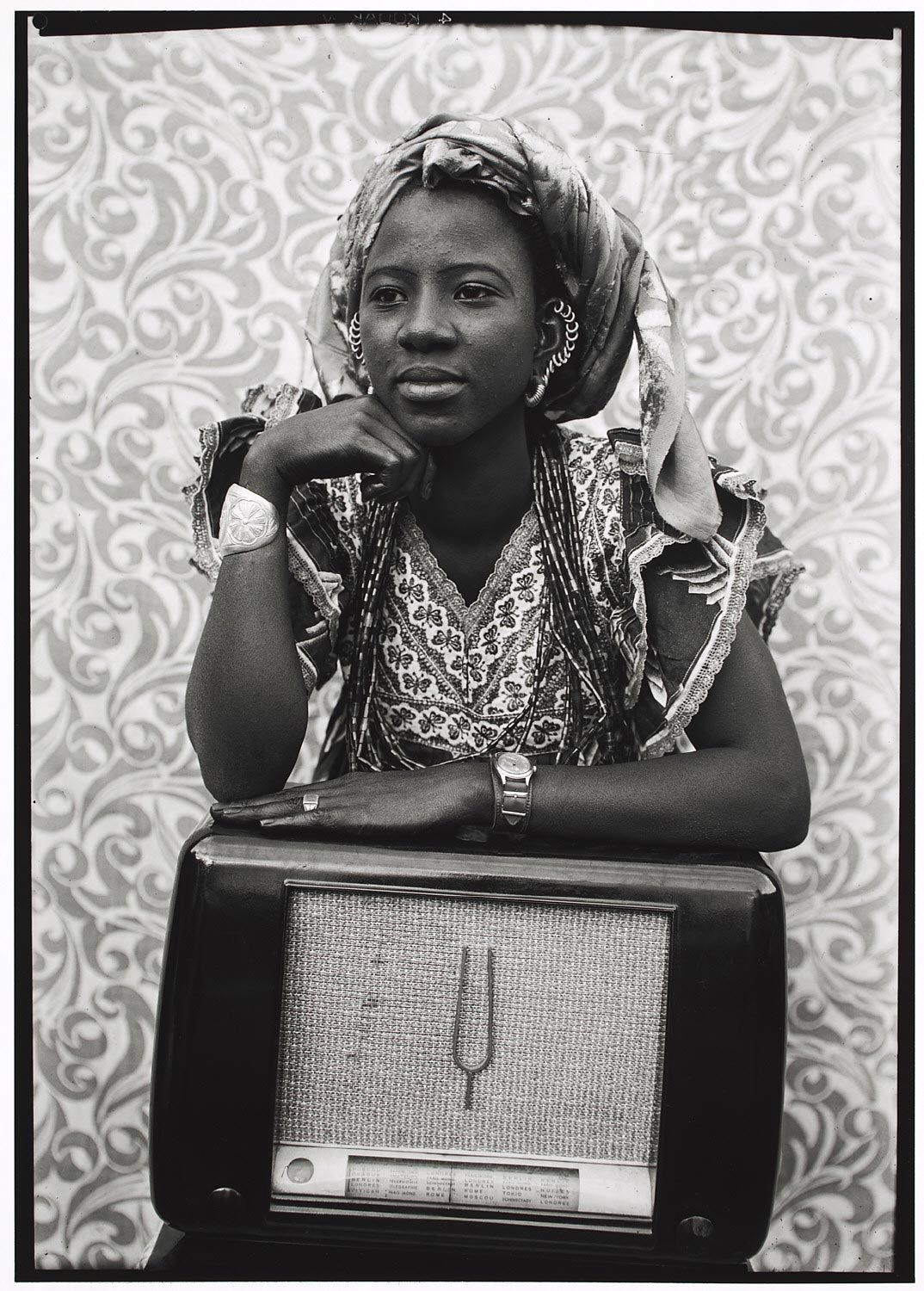

Antawan I. Byrd It developed in this strangely organic way during a graduate seminar I was taking about six years ago. I remember coming across Franz Fanon’s essay, "This is the Voice of Algeria," which is published in a Dying Colonialism (1959). In that essay so many things stood out to me. But there was this one section where he was describing how Algerians were reluctant to embrace the radio early on in the ‘50s, in part, because they had this sort of colonial association with it, there was this sense that it was exclusive – that the French were listening to the French, and radio was a sort of closed space. But then the National Liberation Front began to disseminate leaflets that encouraged people to listen to the radio so that they can get a sense of the revolutions as they were happening across North Africa, but also, to gain knowledge of France’s intentions at the time. And once France got wind of Algerians being attuned to the radio, they began to jam the stations. And so you have this sort of collective listening experience where Algerians are trying to stay apprised of political developments--you can imagine listening to a broadcast, and then at some point, you just get white noise because everything is being jammed. Fanon writes about how people, as a way of maintaining their participation in the revolution, would invent stories that they could have heard over the radio, despite the jamming. And I love that sense of inventiveness. I think Fanon describes it almost as a “true lie.” And I began to think about that in relation to a lot of the writing that I was reading on studio portraiture and how people would go to the studio and invent personas for themselves, they would embody different characters, and that was supported by props and ornate backdrops that they would stand before. And so this sense of invention, and subjectivity as it relates to both the listening experience, whether it's on a national level, or just sort of aesthetic preferences that a lot of clients had, as they entered the studio, seemed to collide for me - that sense of the true lie, it essentially raised a question of whether or not people were actually listening to radio sets at the time that they were being photographed. Or if they wanted to give the impression that they were. And so there's this possibility that, you know, when you look at the photographs by Sidibé, or Keïta, or numerous other photographers, and people are posing with these transistor radios, these large tabletop Bakelite radio sets, that they could be listening to something or the machine could not be working at all and it's just the impression that you want to convey through the image as a listening subject. I like that tension a great deal, and I began to press on it a bit more to try to figure out what the sort of political associations with radio broadcasting and Francophone West Africa at the time that these studio practitioners were really taking off during the 40s and 50s. And to me, there was a very clear sense that not only was the radio set something that people were thinking of as a modern technology, but they turned to photography to celebrate their consumption of that technology. But also, it was a politicised technology. A lot of Francophone and Pan-African organisations like the RDA were very astute at how they could use the radio as a way of disseminating anti-colonial propaganda. And so that's where the research sort of took off. Since then it's led to so many other areas and sort of micro fascinations with things, like, plastic and the materiality of Bakelite and the synthetic nature of it, and how that relates to the artifice of studio photography.

Antawan I. Byrd It developed in this strangely organic way during a graduate seminar I was taking about six years ago. I remember coming across Franz Fanon’s essay, "This is the Voice of Algeria," which is published in a Dying Colonialism (1959). In that essay so many things stood out to me. But there was this one section where he was describing how Algerians were reluctant to embrace the radio early on in the ‘50s, in part, because they had this sort of colonial association with it, there was this sense that it was exclusive – that the French were listening to the French, and radio was a sort of closed space. But then the National Liberation Front began to disseminate leaflets that encouraged people to listen to the radio so that they can get a sense of the revolutions as they were happening across North Africa, but also, to gain knowledge of France’s intentions at the time. And once France got wind of Algerians being attuned to the radio, they began to jam the stations. And so you have this sort of collective listening experience where Algerians are trying to stay apprised of political developments--you can imagine listening to a broadcast, and then at some point, you just get white noise because everything is being jammed. Fanon writes about how people, as a way of maintaining their participation in the revolution, would invent stories that they could have heard over the radio, despite the jamming. And I love that sense of inventiveness. I think Fanon describes it almost as a “true lie.” And I began to think about that in relation to a lot of the writing that I was reading on studio portraiture and how people would go to the studio and invent personas for themselves, they would embody different characters, and that was supported by props and ornate backdrops that they would stand before. And so this sense of invention, and subjectivity as it relates to both the listening experience, whether it's on a national level, or just sort of aesthetic preferences that a lot of clients had, as they entered the studio, seemed to collide for me - that sense of the true lie, it essentially raised a question of whether or not people were actually listening to radio sets at the time that they were being photographed. Or if they wanted to give the impression that they were. And so there's this possibility that, you know, when you look at the photographs by Sidibé, or Keïta, or numerous other photographers, and people are posing with these transistor radios, these large tabletop Bakelite radio sets, that they could be listening to something or the machine could not be working at all and it's just the impression that you want to convey through the image as a listening subject. I like that tension a great deal, and I began to press on it a bit more to try to figure out what the sort of political associations with radio broadcasting and Francophone West Africa at the time that these studio practitioners were really taking off during the 40s and 50s. And to me, there was a very clear sense that not only was the radio set something that people were thinking of as a modern technology, but they turned to photography to celebrate their consumption of that technology. But also, it was a politicised technology. A lot of Francophone and Pan-African organisations like the RDA were very astute at how they could use the radio as a way of disseminating anti-colonial propaganda. And so that's where the research sort of took off. Since then it's led to so many other areas and sort of micro fascinations with things, like, plastic and the materiality of Bakelite and the synthetic nature of it, and how that relates to the artifice of studio photography.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled #851 (Woman with Radio), ca. 1956-1957. © Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali. Courtesy: Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Sean Kelly Gallery, New York and J.M. Patras, Paris.

Tsitsi Jaji I'm looking at the images of Seydou Keïta, and these women are in this intimate, close pose, listening to the radio, or sitting with the radio, standing I think with the radio, it had never occurred to me actually to wonder, are they listening? Or not? Is this a piece of furniture, a kind of prosthesis of their hipness, their modernity, of their insisting that there isn't a contradiction between their outfits? which are these beautiful, you know, outfits that are referencing, with their headdress with the prints, etc, their pride in contemporary vernacular or indigenous, African aesthetics, right. And yet, they're so comfortable with the radio, and they're sitting on top of it in a way, you know, like, they've got their hand on top of it, they're propping their heads up in a way that gives us a sense that they're thinking, they're pensive -- like, literally, that's the thinker pose, you know -- and so peaceful, confident. We don't know what's going through their minds. And I'm also struck that in two of the three images we see here they're wearing a watch, you know, and a watch, and bangles, that are more traditional. So I'm starting to understand how much one can read in these images from the way that you're talking about them. And it reminds me of another idea that we've both engaged with, which is synesthesia. And the sense that there isn't an opposition between sensory modes. And, of course, like the idea that one has five separate senses for some very Western and contemporary idea. how is this thing a given that you're experiencing an apple through taste, or what have you? Like that we're only looking at these images right now, and not worrying about background sounds that we're hearing in our homes in this particular moment. There's something also about thinking of how a moment in time can be so saturated with the senses, and with a kind of coherence, even in the experience among senses that now I'm starting to think maybe that's one of those things that makes me so interested in these images of signs of African modernity. And it's a modernity, on its own terms, it's in no way anxious about what the intimacy between that Bakelite radio, and a young African woman's body would be.

Antawan I. Byrd You know, one of the things I love about that is, there’s this funny story, a story I’ve thought about in so many different ways. There's an interview, I think it was published in NKA maybe around 2008, it may have been a reproduced interview from another source, I can't remember, but it's with Malick Sidibé and he's talking about, you know, the way that women would come into the photography studio. And one of the things he says is that of course they would get dressed up, and they would have makeup on and, you know, their hair would be really nicely done, and they'd be adorned with jewelry and things like that. But he said that they also put on perfume--that they put on perfume, in some instances right before the photograph is going to be taken. And to me, that blows my mind because obviously, you can't smell, you know, sandalwood or vetiver or whatever fragrance, you can't smell that through the image. But it was enough for the subject to feel that somehow it may change their sensibility, or their comportment or their sense of comfort. Or that, you know, after the photograph was taken, maybe they could look back to that image. And remember what it smelled like at the moment of having their portrait taken. And to me it has that same sort of souvenir or kind of mnemonic function in relation to sound. I like the idea that you could look at one of these images or that the subject could look at themselves, you know, 30 years later, and somehow remember the conversations that they were having with the photographer, or maybe with other clients who were waiting in line just before they had their picture taken.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, that's fantastic, because we know that smell is a really strong mnemonic sense, you might lose other kinds of memories, and particularly memories connected to language, but a smell, can bring you back to a moment. And that's a really important thing for older people who are struggling with memory. And it's the same with music. So as you're talking about this, I'm really also struck by this, we think of it as a snapshot of a moment, but like you're saying, it's a whole stretch of time and of possibility and of memory. And especially when we're looking back on that moment of independence, and whatever the frontier of possibility that invest these periods with nostalgia, that they are also periods, when one looks back on, one has a whole set of reflections, interpretations, etc. And so to be listening to the radio in this moment, whether it's UDI which I think, you know, they must have been smelling the scent of the earth, whether it's the drying of the dust or that saturation right after its rained, or whatever it was, that's a piece of a photograph, right, and that's a piece of what's integrated into each of their memories and into the stories they may or may not tell to their family members and trade with each other, remember with each other. That's the other thing about radios, right? And radio music is something you don't listen alone, and certainly back then people didn't listen alone in the way that we are with our headphones, and that it's a collective memory, even if you're looking at one woman listening to one radio set, it's just like that Fanon moment, right. There's a collectivity that comes into being when people are all listening together in their own spaces, to the same music, or radio broadcasts or news, or what have you. It's just that these images radiate in so many different ways, across time and space, and the intersections between those two.

Antawan I. Byrd Yeah, and it also makes me think of this phenomenon of pavement radio, or street radio, and how even you could have this collective experience of listening, whether it's its people surrounded, surrounding a radio set in a specific place, or the sense that it becomes collective by word of mouth, by, you know, this, experience of listening, somehow being transmitted from one ear to the next, or even a conversation about what people have heard over the radio at separate moments. But that being the basis of a kind of social experience, which I think is fascinating, and it makes me, of course, think about YouTube and different sort of television moments that we all sort of collectively discuss and embrace as we think about how earlier technologies allowed for a similar experience of sociality, I think is there's something magical about it.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, this is so rich, to think about because like you're saying, the radio generates waves of thinking is a pavement radio idea, you know, that it's not that the speech comes first. It's this technology and this urban kind of feeling, right, even a kind of crowdedness that's so tied to the pleasure that people take and rumour and gossip, in jokes, right, that they have this way as well. And those jokes are so often also connected to contemporary moments.

So can you talk just a little bit more about the fact that these are women in these images? That seems to matter.

Antawan I. Byrd By and large, I mean, there's one instance in Keïta's sort of portraiture where there's a man who appears with a radio set. But more often than not, you're right, I've seen more examples of women than I have of men. And a part of me likes to think of it in terms of the sort of aesthetic appeal of the machine and the way that it resonates with the jewellery that the women are wearing. So for instance, one of the things that I've always liked is the way that the machine itself is shiny--how it's sort of optically appealing, in the same way that the woman's jewellery is. And so you have that kind of resonance. But it also makes me think of the ways women may be more conscious, or desirous of emphasising their participation in modernity in this way... And so yes, so that's one idea that comes to mind. But it also makes me think about your work and your interests and the Telefunken Radio advertisements.

Antawan I. Byrd You know, one of the things I love about that is, there’s this funny story, a story I’ve thought about in so many different ways. There's an interview, I think it was published in NKA maybe around 2008, it may have been a reproduced interview from another source, I can't remember, but it's with Malick Sidibé and he's talking about, you know, the way that women would come into the photography studio. And one of the things he says is that of course they would get dressed up, and they would have makeup on and, you know, their hair would be really nicely done, and they'd be adorned with jewelry and things like that. But he said that they also put on perfume--that they put on perfume, in some instances right before the photograph is going to be taken. And to me, that blows my mind because obviously, you can't smell, you know, sandalwood or vetiver or whatever fragrance, you can't smell that through the image. But it was enough for the subject to feel that somehow it may change their sensibility, or their comportment or their sense of comfort. Or that, you know, after the photograph was taken, maybe they could look back to that image. And remember what it smelled like at the moment of having their portrait taken. And to me it has that same sort of souvenir or kind of mnemonic function in relation to sound. I like the idea that you could look at one of these images or that the subject could look at themselves, you know, 30 years later, and somehow remember the conversations that they were having with the photographer, or maybe with other clients who were waiting in line just before they had their picture taken.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, that's fantastic, because we know that smell is a really strong mnemonic sense, you might lose other kinds of memories, and particularly memories connected to language, but a smell, can bring you back to a moment. And that's a really important thing for older people who are struggling with memory. And it's the same with music. So as you're talking about this, I'm really also struck by this, we think of it as a snapshot of a moment, but like you're saying, it's a whole stretch of time and of possibility and of memory. And especially when we're looking back on that moment of independence, and whatever the frontier of possibility that invest these periods with nostalgia, that they are also periods, when one looks back on, one has a whole set of reflections, interpretations, etc. And so to be listening to the radio in this moment, whether it's UDI which I think, you know, they must have been smelling the scent of the earth, whether it's the drying of the dust or that saturation right after its rained, or whatever it was, that's a piece of a photograph, right, and that's a piece of what's integrated into each of their memories and into the stories they may or may not tell to their family members and trade with each other, remember with each other. That's the other thing about radios, right? And radio music is something you don't listen alone, and certainly back then people didn't listen alone in the way that we are with our headphones, and that it's a collective memory, even if you're looking at one woman listening to one radio set, it's just like that Fanon moment, right. There's a collectivity that comes into being when people are all listening together in their own spaces, to the same music, or radio broadcasts or news, or what have you. It's just that these images radiate in so many different ways, across time and space, and the intersections between those two.

Antawan I. Byrd Yeah, and it also makes me think of this phenomenon of pavement radio, or street radio, and how even you could have this collective experience of listening, whether it's its people surrounded, surrounding a radio set in a specific place, or the sense that it becomes collective by word of mouth, by, you know, this, experience of listening, somehow being transmitted from one ear to the next, or even a conversation about what people have heard over the radio at separate moments. But that being the basis of a kind of social experience, which I think is fascinating, and it makes me, of course, think about YouTube and different sort of television moments that we all sort of collectively discuss and embrace as we think about how earlier technologies allowed for a similar experience of sociality, I think is there's something magical about it.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, this is so rich, to think about because like you're saying, the radio generates waves of thinking is a pavement radio idea, you know, that it's not that the speech comes first. It's this technology and this urban kind of feeling, right, even a kind of crowdedness that's so tied to the pleasure that people take and rumour and gossip, in jokes, right, that they have this way as well. And those jokes are so often also connected to contemporary moments.

So can you talk just a little bit more about the fact that these are women in these images? That seems to matter.

Antawan I. Byrd By and large, I mean, there's one instance in Keïta's sort of portraiture where there's a man who appears with a radio set. But more often than not, you're right, I've seen more examples of women than I have of men. And a part of me likes to think of it in terms of the sort of aesthetic appeal of the machine and the way that it resonates with the jewellery that the women are wearing. So for instance, one of the things that I've always liked is the way that the machine itself is shiny--how it's sort of optically appealing, in the same way that the woman's jewellery is. And so you have that kind of resonance. But it also makes me think of the ways women may be more conscious, or desirous of emphasising their participation in modernity in this way... And so yes, so that's one idea that comes to mind. But it also makes me think about your work and your interests and the Telefunken Radio advertisements.

Telefunken radio advertisements 1959 “Raky est sérieuse; Raky est heureuse; Raky est moderne.” Courtesy: M. de Breteiul, former publisher of Bingo.

Tsitsi Jaji These were a series of advertisements, there were three examples that I've seen, I don't believe they're more because I really poured over these magazines. But they appeared in a magazine called "Bingo" which was published out of Dakar and Paris but circulated widely. And so the main character in these images is Raky. And in one of them, she's serious, in one of them, she's happy, in one of them, she's modern. Now, I'll just show you that serious one first, because the intensity of her focus on the radio and the fact that her hand is on the dial, I think is really striking to me, and the detail of the print and this one, again, really signalling her Africanness and kind of picking up on the pattern of the radio speaker itself, you know, that rhythm in both of these. And she's at home, from what we can tell in this image where it's marked as home, the domestic space, the kind of furniture, the lamp, whether or not that was how people were constructing their domestic space in this moment in Dakar, we can question but it's important in this ad, that she looks at home with technology, you know, and that she's a thinker, again, like the the images that you showed, and then I want to look at another image and this is the one of Raky being modern, and the sort of caption and again, these are just cell radios and they are coming from a company based in Germany, etc. So it's also selling an idea of consumption as the modus operandi of being up to date in Africa at this moment, but this here says, “Raky is modern. She wants to know everything. She's always listening to the radio, her radio works really well. It's beautiful. And it's sonorous.” So she wants to know, you know, and that again, I think really matters. It's interesting that in this version, the modern Raky doesn't seem to be wearing African dress. Although we all know that whatever the style is, if an African is wearing it, it's African dress, right. But in this one, she's staring right at us, still with her hand on the radio, you know, her posture kind of leaning in, and so comfortable. And yet it also looks as if maybe we and her have a little bit of a conspiracy going on, like we know something about that radio. And it's a different knowing than the knowing the caption seems to be saying. But it also gets at this idea of listening together. And that sociality, and even that sociality bursting through the pages of a magazine that's trying to advertise consumption in a particular way.

Antawan I. Byrd I think, I mean, several things come to mind. I’m thinking about that first image of Raky where she's looking at the machine. And I think it's interesting, because you have this sense that, you know, listening is also a visual experience in the sense that you have to be attentive to the device in order to turn the dial. And in some of the earlier sort of bulkier radio sets that I've been studying, a lot of them had, you know, the country names or city names on their tuner scales. And so you're looking at it, and basically, you're navigating the world, as you figure out, which country or which broadcast you want to listen to. So I like this image, because it seems to evoke that early sort of history of travel in a way by virtue of radio listening.

Tsitsi Jaji The other thing, I've never thought about the line in these ads, and it comes up in all of them, is that she wants the radio to be beautiful and sound good. It's not just the sounding of it that matters. And, that's a lovely thing to be able to notice.

Antawan I. Byrd And I want to bet that sense of beautiful--it brings me back to these Keïta images. Keïta unfortunately, never spoke explicitly about the radio sets, I think there are some interviews where he said that he had bought one or two of them or something like that. But he never spoke about whether or not they were being powered on at the time of the portrait session, or where he acquired them or anything. But, you know, from Keïta's interviews I sense he was very savvy as a businessman--he realised that, you know, buying these different props, these modern objects was a way of enticing his clients to want to pose with these machines, you see that in these images, I think it's very strategic the way that the radio set is pushed up against the picture plane. And it's almost level with the presence of the subject. And so, as you're reading the image, especially here, you're reading the radio and the subject together, that they're somehow intertwined or fused... Yeah, it's beautiful, you sense the machine is beautiful, and the subject is beautiful. And because of that, the image is beautiful. And I just like that kind of interplay.

Tsitsi Jaji So I want to ask you, and I know we'll probably wrap up our conversation sooner than I would like -- it's so fun to talk with you. But you're spending all this time looking at images from a particular moment. Does it make you think differently about contemporary listening, especially among such diverse kinds of media? Or do you see any through lines there?

Antawan I. Byrd Um, I think there's a, there was a moment where I was really interested in the Arab Spring, and in North Africa, and trying to figure out how there might be connections between, let's say, social media, and the way that people were listening in to sort of political developments. Listening through Twitter, I guess you could say, and if that could be connected to, you know, the 1950s and the way that people were also being attentive to developments by way of the radio. So that's something that comes to mind. And I also think about, you know, the sense of mobility. And how now I'm listening to you with my airpods. And so I'm somehow detached from a cord and I'm able to move around. And I think about that in relation to, you know, early histories of studio portraiture and the 1930s and 40s. And the mobility that the image had, its ability to be sent across borders. And in some cases, you know, there are instances where someone would send a radio to someone, in let's say, West Africa, from France, and then they would photograph themselves with their radio set, and then send the photograph back as evidence of having received the gift. So I like to think of the portability of the image and broadcasting and movement in earlier times, as it relates to today, and the way that we can just consume sound and listen with such ease and flexibility. Very different realities. But I think there's an interesting link here just in terms of circulation.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, for sure. You know, as you're speaking, it makes me think about one of the WhatsApp groups that I subscribe to is called Kukurigo. And it's one way to keep up with news happening in Zimbabwe, you know all of these things, they're edited, etc, but living in the diaspora. This is one where, as somebody who's not comfortable on Twitter, I can get like a very streamlined digest. And among the things that it sends out, on the WhatsApp is read every day, the VOA Voice of America, news broadcasts in English, Ndebele, and Shona. So among the many things that are circulating there is a reminder of the global circulations and how messy they are, etc. Washington D. C, sponsors it and they always announce that that's where it's broadcasting from information, for Zimbabweans on the ground, that people in the diaspora are listening in on etc, etc. But it's also being heard in all three of these dominant national languages, obviously, we have other minority languages, but you know, it's circulating in the same piece of technology that I take and look at pretty much all the images that I have a personal connection to, you know, so it's like, on the one hand, like you're saying, that moment was so specific, but it almost predicts or makes coherent, some of what we do with our technology today.

Antawan I. Byrd Yeah, and it seems like a natural progression. I mean, when you think about, like, I don't know the transistor radio, and how small they got around like the 1960s. And the way that people would be able to carry them around. In fact, there are a lot of studio portraits I've seen where people would come in with, you know, a transistor radio inside of a bespoke bag. And they would have the bag on their shoulder as they would pose for a picture. But the sense that, yeah, [the subject] wants you to know that they have this immediate access to information and the craving is so strong, that you know, you design a sort of pack to carry your radio set in. So I feel like that's, that's, that's an analogue to the iPhone, and the ability to listen to podcasts.

Tsitsi Jaji It's funny, too. I know, like I said, that we're probably gonna have to wrap up, but I'm remembering, I spent some months in Dakar in 2007. And it was probably happening all over at the time, but I'd be in these car rapides, nice and packed in like sardines. And people were listening, young people were listening to mp3, on their own phones, with headphones in this really crowded social space. And I hadn't seen that anywhere else. And so it was this cutting edge use of technology that was not lagging behind the West, but kind of reconstructing what one could do in a space, that because of how bodily intimate you were, you couldn't not be aware of the closeness and you know, the multi sensory experience we all know from being crowded in certain spaces, including the perfumes that emanate. You know, like it was just every day, it was just how you get from one place to another. You don't do it in silence, or in that particular noisiness that doesn't already have multimedia and multiple signals in it.

Shall we say goodbye, and to be continued? and to just thank Njelele for bringing us into conversation together.

Antawan I. Byrd This has been fantastic. I am really happy, and think these ideas that are present in both of our work have infinite applicability to a lot of other phenomena, so I'm looking forward to seeing where it develops.

Tsitsi Jaji Stay well.

Antawan I. Byrd I think, I mean, several things come to mind. I’m thinking about that first image of Raky where she's looking at the machine. And I think it's interesting, because you have this sense that, you know, listening is also a visual experience in the sense that you have to be attentive to the device in order to turn the dial. And in some of the earlier sort of bulkier radio sets that I've been studying, a lot of them had, you know, the country names or city names on their tuner scales. And so you're looking at it, and basically, you're navigating the world, as you figure out, which country or which broadcast you want to listen to. So I like this image, because it seems to evoke that early sort of history of travel in a way by virtue of radio listening.

Tsitsi Jaji The other thing, I've never thought about the line in these ads, and it comes up in all of them, is that she wants the radio to be beautiful and sound good. It's not just the sounding of it that matters. And, that's a lovely thing to be able to notice.

Antawan I. Byrd And I want to bet that sense of beautiful--it brings me back to these Keïta images. Keïta unfortunately, never spoke explicitly about the radio sets, I think there are some interviews where he said that he had bought one or two of them or something like that. But he never spoke about whether or not they were being powered on at the time of the portrait session, or where he acquired them or anything. But, you know, from Keïta's interviews I sense he was very savvy as a businessman--he realised that, you know, buying these different props, these modern objects was a way of enticing his clients to want to pose with these machines, you see that in these images, I think it's very strategic the way that the radio set is pushed up against the picture plane. And it's almost level with the presence of the subject. And so, as you're reading the image, especially here, you're reading the radio and the subject together, that they're somehow intertwined or fused... Yeah, it's beautiful, you sense the machine is beautiful, and the subject is beautiful. And because of that, the image is beautiful. And I just like that kind of interplay.

Tsitsi Jaji So I want to ask you, and I know we'll probably wrap up our conversation sooner than I would like -- it's so fun to talk with you. But you're spending all this time looking at images from a particular moment. Does it make you think differently about contemporary listening, especially among such diverse kinds of media? Or do you see any through lines there?

Antawan I. Byrd Um, I think there's a, there was a moment where I was really interested in the Arab Spring, and in North Africa, and trying to figure out how there might be connections between, let's say, social media, and the way that people were listening in to sort of political developments. Listening through Twitter, I guess you could say, and if that could be connected to, you know, the 1950s and the way that people were also being attentive to developments by way of the radio. So that's something that comes to mind. And I also think about, you know, the sense of mobility. And how now I'm listening to you with my airpods. And so I'm somehow detached from a cord and I'm able to move around. And I think about that in relation to, you know, early histories of studio portraiture and the 1930s and 40s. And the mobility that the image had, its ability to be sent across borders. And in some cases, you know, there are instances where someone would send a radio to someone, in let's say, West Africa, from France, and then they would photograph themselves with their radio set, and then send the photograph back as evidence of having received the gift. So I like to think of the portability of the image and broadcasting and movement in earlier times, as it relates to today, and the way that we can just consume sound and listen with such ease and flexibility. Very different realities. But I think there's an interesting link here just in terms of circulation.

Tsitsi Jaji Yeah, for sure. You know, as you're speaking, it makes me think about one of the WhatsApp groups that I subscribe to is called Kukurigo. And it's one way to keep up with news happening in Zimbabwe, you know all of these things, they're edited, etc, but living in the diaspora. This is one where, as somebody who's not comfortable on Twitter, I can get like a very streamlined digest. And among the things that it sends out, on the WhatsApp is read every day, the VOA Voice of America, news broadcasts in English, Ndebele, and Shona. So among the many things that are circulating there is a reminder of the global circulations and how messy they are, etc. Washington D. C, sponsors it and they always announce that that's where it's broadcasting from information, for Zimbabweans on the ground, that people in the diaspora are listening in on etc, etc. But it's also being heard in all three of these dominant national languages, obviously, we have other minority languages, but you know, it's circulating in the same piece of technology that I take and look at pretty much all the images that I have a personal connection to, you know, so it's like, on the one hand, like you're saying, that moment was so specific, but it almost predicts or makes coherent, some of what we do with our technology today.

Antawan I. Byrd Yeah, and it seems like a natural progression. I mean, when you think about, like, I don't know the transistor radio, and how small they got around like the 1960s. And the way that people would be able to carry them around. In fact, there are a lot of studio portraits I've seen where people would come in with, you know, a transistor radio inside of a bespoke bag. And they would have the bag on their shoulder as they would pose for a picture. But the sense that, yeah, [the subject] wants you to know that they have this immediate access to information and the craving is so strong, that you know, you design a sort of pack to carry your radio set in. So I feel like that's, that's, that's an analogue to the iPhone, and the ability to listen to podcasts.

Tsitsi Jaji It's funny, too. I know, like I said, that we're probably gonna have to wrap up, but I'm remembering, I spent some months in Dakar in 2007. And it was probably happening all over at the time, but I'd be in these car rapides, nice and packed in like sardines. And people were listening, young people were listening to mp3, on their own phones, with headphones in this really crowded social space. And I hadn't seen that anywhere else. And so it was this cutting edge use of technology that was not lagging behind the West, but kind of reconstructing what one could do in a space, that because of how bodily intimate you were, you couldn't not be aware of the closeness and you know, the multi sensory experience we all know from being crowded in certain spaces, including the perfumes that emanate. You know, like it was just every day, it was just how you get from one place to another. You don't do it in silence, or in that particular noisiness that doesn't already have multimedia and multiple signals in it.

Shall we say goodbye, and to be continued? and to just thank Njelele for bringing us into conversation together.

Antawan I. Byrd This has been fantastic. I am really happy, and think these ideas that are present in both of our work have infinite applicability to a lot of other phenomena, so I'm looking forward to seeing where it develops.

Tsitsi Jaji Stay well.